Nyhedsanalysen

Middle Eastern Asylum Seekers Forcibly Relocated With As Little As 24 Hours Notice To Make Room For Ukrainians

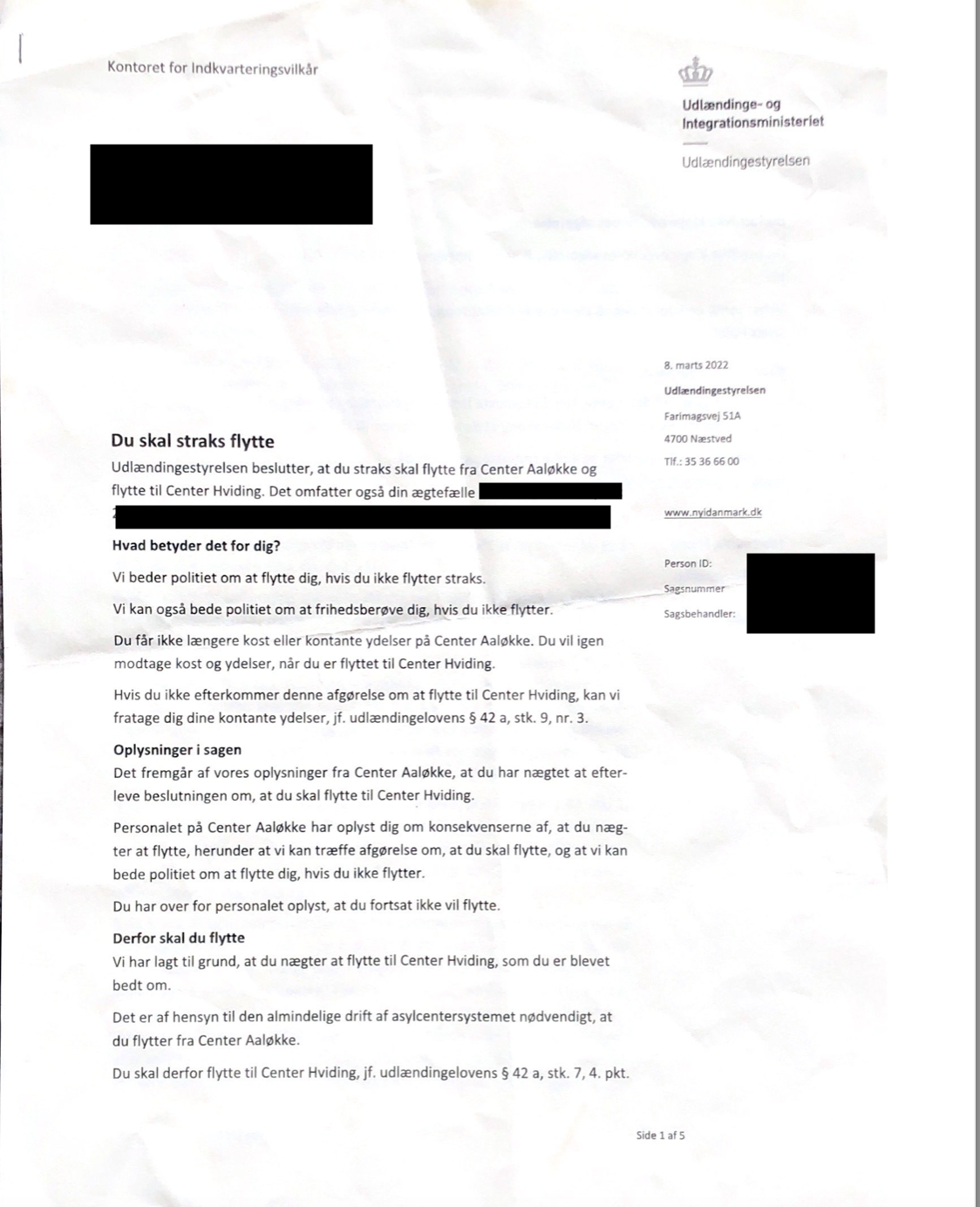

The Al-Ashqi's family's eviction notice which features threats of police involvement.

(THE ARTICLE WAS PUBLISHED IN DANISH ON MARCH 25TH 2022 IN FØLJETON. THIS IS A TRANSLATION. ORIGINAL ARTICLE HERE)

23-year-old Hussein Al-Ashqi calls from the small room he shares with his parents at Asylum Center Hviding in Tønder municipality. The crammed, dimly lit space has been their home since March 8th 2022. 24 hours prior to the move they had received notice that they were to pack up their apartment of three years at Asylum Center Aaløkke and get ready to move to the room they now call home. If they didn’t comply, police would be involved. Their old place is now housing a larger Ukrainian family, who came to Denmark in the wake of Russia’s war on Ukraine.

“We were asked to move within 24 hours. We have lived here for three years, how can you pack up that life in 24 hours? My parents are sick, so there was only me to do it. I asked for two days to get it done and was turned down. My dad had a doctor’s appointment the next day. They canceled it and we had to move instead,” Hussein says over the phone.

According to Hussein, his protest triggered verbal threats of police involvement from the center’s accommodation operator. These threats were subsequently followed up by the Danish Immigration Service in a written relocation order: “The Immigration Department has decided that you must immediately move from Asylum Center Aaløkke to Asylum Center Hviding”, says the letter, which Føljeton is in possession of. “We will ask the police to move you if you do not voluntarily do so immediately. We can also order the police to detain you if you do not move.” The threat of police involvement, Hussein says, particularly frightened his parents, who both suffer from poor physical, and in his mother’s case, mental health. For the whole family, it created a sense of being pushed aside in favor of the new arrivals.

On March 4th, a Statutory Law came into force making it easier for Ukrainian refugees to integrate into Danish society. The government’s supporting parties voted in favor of the bill without exception, although the drafting of the law received criticism from both The Red-Green Alliance and The Social Liberal Party. According to the two parties, the need for special legislation favoring Ukrainian refugees points to general problems in the asylum system’s general treatment of refugees.

At the receiving end of this is the Al-Ashqi family who is left with a concrete feeling of having been disfavored by the Danish asylum system: “A refugee is a refugee, but our kind of refugees are threatened with police involvement. I no longer know if the police are there to protect me or to scare me,” says Hussein.

The director of Aaløkke Asylum Centre denies that discrimination takes place at the centre: “We meet people in exactly the same way, regardless of where they come from.” She does not want to comment on whether the Al-Ashqi family has been verbally threatened with police interference by the facility’s staff, referring instead to the Danish Immigration Service which is responsible for sending out notices to asylum seekers. In a written response, the Department informs Føljeton that the threat of police involvement in the written warning is standard procedure:

“People who have to move have the right to know that there is no freedom of choice as to whether they want to move. Therefore, it is legitimate – also in the interest of the resident being moved – to inform about the possibilities for action by the authorities in case persons who are to move refuse to cooperate.” The Danish Immigration Service has not responded to Føljeton’s inquiries about the need to prominently feature risk of police involvement in an initial notice of removal.

“The result of years of trying to make refugees feel as unwelcome as possible“

In contrast to the Al-Ashaqi family’s story, the Danish Immigration Service writes that the family received a verbal notice on March 7th and that the process took place in the span of 48 hours rather than 24 hours. At Aaløkke Centre they do, however, admit that asylum seekers may receive as little as 24 hours’ notice prior to a forced relocation. According to Rosa Lund (MP), spokesperson for integration for the Red-Green Alliance, this is the result of a dire lack of resources in the Danish asylum system:

“For years we have been reducing the capacity of the Danish asylum system. This means that when there is a large influx of refugees, we do not have the space, and so we have to ask people to move. And I think that people should get a proper warning of course. What I think we can learn from this is that we should not have closed down asylum centers, because you cannot predict when some dictator is going to run amok or when the Taliban is going to take over. So I think this should be a reminder to Minister of Immigration Mattias Tesfaye that closing asylum centers is a bad idea.”

The spokesperson for integration at The Social Liberal Party Kathrine Olldag agrees that the influx in immigration as a result of the war in Ukraine may lead to the relocation of other refugees: “But you have to do it properly. And you have to treat people with respect, regardless of where they come from. It shouldn’t be the case that the authorities persist in using harassing administrative language.”

Lund says the threat of police involvement in cases of forced relocations is disproportionate: “I don’t see why the police should be involved at all. We are talking about people who are on the run. I think the Red Cross, for example, can handle it much better and much more gently with the people in question.”

Olldag also criticizes the procedure: “It’s inhumane, but unfortunately it’s the result of years of trying to make refugees feel as unwelcome as possible. And that’s why at some point you see the emergence of these extremely harassing procedures.”

Aaløkke’s relocation of a family of Middle Eastern descent is not unique. Around the country’s asylum centers there are a number of asylum seekers who right now feel as if they are being neglected in favor of Ukrainian refugees. Lund believes that their feelings are accurate:

“Exactly the same thing happened when the Afghans arrived in August 2021, because we have been so stingy with the capacity of the Danish asylum system,” Lund says.

At the same time she stands by the fact that The Red-Green Alliance voted in favor of the Statutory Law, which enables special treatment of Ukrainians in the asylum system: ‘We didn’t really have any other choice. It is difficult for a party that wants better treatment of refugees to vote ‘no’ when there is finally a majority in favor of better treatment of refugees – even if it is not for everyone. And I actually think we can use this to uplift others.“

It has not been possible to obtain information from the Danish Immigration Service on how many residents of an ethnicity other than Ukrainian have so far been forcibly evicted to make room for the new arrivals. Last week, however, Politiken reported on 15 cases at Asylum Center Sjælsmark alone. Here, too, extremely short deadlines for the relocations were reported.

According to the Al-Ashaqi family’s lawyer Eva Steinhorst, neither the short deadlines nor the threat of police interference is abnormal. She is part of a network that assists refugees in the asylum system and has witnessed similar cases in the past:

“For asylum seekers, it is often their only option to oppose the move because they do not have access to lawyers. Indeed, the problem is that removals are often structured in such a way that they are given no more than 24 hours to move – a minimal amount of time to coordinate their situation, to contact activists, media or aid organizations, or to get advice from a lawyer. So all they can do is say they don’t want to move. The authorities know this, which is why they threaten with police involvement. But I don’t think that’s justifiable. I have witnessed a situation where the police came to move a family by force and far more officers turned up than what was necessary. So it really is a show of force.”

“I’ve always felt that this place was my place too”

If you ask Hussein, there is no doubt that the Ukrainian refugees should be received in the best possible way. Still he is upset about how the rush of doing so has affected his own family: “It’s unfair. My mother offered that we could house a small family in our apartment at Aaløkke, because we know what war is. But the government doesn’t treat all refugees the same.”

The adjustment to life at Asylum Center Hviding, where the family is now housed, has been tough. Here they have gone from living in a two bedroom apartment to sharing a small room with a bunk bed. The conditions at Hviding are described by several people with whom Føljeton has been in contact as “prison-like”, and this is causing health problems for the family: “My mother cries every day. She is mentally ill and it is difficult. It’s hard for me too, because I can’t do anything for them.”

Palestinian activist Aja Jilani, who was a neighbor of the family at the Aaløkke Centre, has tried to appeal the authorities’ decision because of the family’s fragile position. According to her, the appeal was rejected on the grounds of pressure on the asylum system in light of the war in Ukraine:

“I wrote to the authorities and tried to get the family moved, but was told that it was not possible because of the Ukrainians who need the space. And I understand that. We have sympathy with the Ukrainian refugees. Refugees are refugees. But this family – and a number of other families – also need special help because of illness and trauma.”

The Danish Immigration Service writes that the request was rejected because “[i]t is assessed that the family has the same possibilities to apply for and receive similar health care during the accommodation at Center Hviding as during the accommodation at Center Aaløkke, and that the family’s health conditions should therefore not change the decision to move the family to Center Hviding”.

For Hussein, the first priority now is to get the family moved to a center where conditions are better for his parents. However, he misses his home at Aaløkke: “I have always felt that this place was my place, too. I’m a painter and I did a project there because I wanted to help create a good environment for the refugees. But I don’t feel appreciated or respected now.” /Asta Kongsted

The family did not want to use their real surname in the article. Al-Ashaqi is an alias. The editors are aware of the family’s identity.